Traditionally it has been very difficult to weld together dissimilar materials like glass and metal due to their different thermal properties as the high temperatures and highly different thermal expansions involved cause the glass to shatter.

Currently, glass and metal are often held together with adhesives, but that process is messy, and parts can gradually move out of place. Additionally, “organic chemicals from the adhesive can be gradually released and can lead to reduced product lifetime

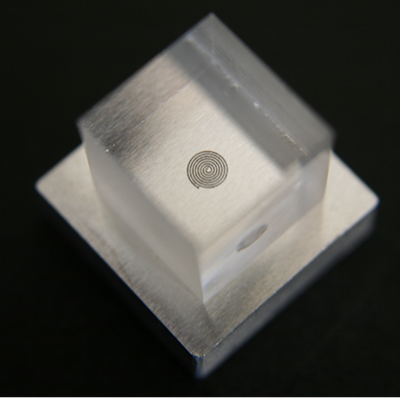

Instead of adhesives, the method Hand and his research team from Heriot-Watt university used to join glass and metal is a technique of recent interest called ultrafast laser micro-welding. Ultrafast laser micro-welding involves aiming laser pulses at the interface between two materials in quick succession so that heat accumulates at the interface and leads to localized melting. When the laser pulses stop and the material re-solidifies, strong and robust bonds form between the materials along the interface.

So far, the majority of research on ultrafast laser micro-welding has focused on similar or slightly dissimilar materials, while research on highly dissimilar materials has concentrated on bonding glass and silicon.

For research on glass and metal welding, Hand and his team explain these previous studies were limited to proof-of-principle demonstrations involving specific material combinations and limited systematic studies. That is why the researchers “aim to move ultrafast micro-welding closer to an industrially viable technique through a systematic study of the parameter space for welding and demonstrating accelerated lifetime survivability,” as they explain in their paper.

However, due to the brittle nature of glass, creating enough samples to produce statistically relevant tests of all parameters was impractical—each process parameter set would require at least 20 samples! So, the researchers chose to focus only on pulse energy and focal plane for this study.

Even just focusing on pulse energy and focal plane, though, would require more than 1,000 individual welds. To limit the number of required samples, the researchers carried out two tests for each pair of parameters to create a parameter map. They used the map to identify regions of interest to run full, 20-sample tests. After running these tests, they identified an “optimized” set of parameters for accelerated lifetime testing.

While the Heriot-Watt press release states various optical materials like quartz, borosilicate glass, and sapphire were all successfully welded to metals like aluminum, titanium, and stainless steel, the actual paper focuses on welding two specific glasses [Spectrosil 2000 (SiO2) and Schott N-BK7 (BK7)] to 6082 aluminum alloy (Al6082).

When discussing the results, one somewhat counter intuitive finding the researchers highlight is that minor cracking around the melt volume (particularly in the glass) indicates a good weld. Cracking is due to the significant difference in thermal expansion between glass and metal—through cracking, glass relieves itself of the thermal stress that occurs during cooling. “[This cracking] does not indicate a reduction in the weld strength,” the authors stress.

In the future, the authors note that further work in thermal compensation, either through interlayers or surface patterning to relieve thermal stress, is needed to develop a reliable welding process, “particularly for material combinations with a large mismatch of thermal expansion, e.g., Al6082–SiO2.”

Currently, glass and metal are often held together with adhesives, but that process is messy, and parts can gradually move out of place. Additionally, “organic chemicals from the adhesive can be gradually released and can lead to reduced product lifetime

Instead of adhesives, the method Hand and his research team from Heriot-Watt university used to join glass and metal is a technique of recent interest called ultrafast laser micro-welding. Ultrafast laser micro-welding involves aiming laser pulses at the interface between two materials in quick succession so that heat accumulates at the interface and leads to localized melting. When the laser pulses stop and the material re-solidifies, strong and robust bonds form between the materials along the interface.

So far, the majority of research on ultrafast laser micro-welding has focused on similar or slightly dissimilar materials, while research on highly dissimilar materials has concentrated on bonding glass and silicon.

For research on glass and metal welding, Hand and his team explain these previous studies were limited to proof-of-principle demonstrations involving specific material combinations and limited systematic studies. That is why the researchers “aim to move ultrafast micro-welding closer to an industrially viable technique through a systematic study of the parameter space for welding and demonstrating accelerated lifetime survivability,” as they explain in their paper.

However, due to the brittle nature of glass, creating enough samples to produce statistically relevant tests of all parameters was impractical—each process parameter set would require at least 20 samples! So, the researchers chose to focus only on pulse energy and focal plane for this study.

Even just focusing on pulse energy and focal plane, though, would require more than 1,000 individual welds. To limit the number of required samples, the researchers carried out two tests for each pair of parameters to create a parameter map. They used the map to identify regions of interest to run full, 20-sample tests. After running these tests, they identified an “optimized” set of parameters for accelerated lifetime testing.

While the Heriot-Watt press release states various optical materials like quartz, borosilicate glass, and sapphire were all successfully welded to metals like aluminum, titanium, and stainless steel, the actual paper focuses on welding two specific glasses [Spectrosil 2000 (SiO2) and Schott N-BK7 (BK7)] to 6082 aluminum alloy (Al6082).

When discussing the results, one somewhat counter intuitive finding the researchers highlight is that minor cracking around the melt volume (particularly in the glass) indicates a good weld. Cracking is due to the significant difference in thermal expansion between glass and metal—through cracking, glass relieves itself of the thermal stress that occurs during cooling. “[This cracking] does not indicate a reduction in the weld strength,” the authors stress.

In the future, the authors note that further work in thermal compensation, either through interlayers or surface patterning to relieve thermal stress, is needed to develop a reliable welding process, “particularly for material combinations with a large mismatch of thermal expansion, e.g., Al6082–SiO2.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed